He was one the most important businessman in the Korea history. He was born on Feb. 11, 1912. At that time, most Koreans were suffering from many difficulties. Less than two decades after having been opened by Commodore Perry, Japan first made its ambitions about Korea known by forcing the country open to trade in 1876. Defeating Russia in the war of 1905, Japan virtually annexed Korea, which was made official five years later.

The colonial government implemented industrial policy. The structure of the colonial economy has been shifting away from agriculture towards manufacturing ever since the beginning of the colonial rule at a consistent pace. Major causes of the structural change included diffusion of modern manufacturing technology, the world agricultural depression shifting the terms of trade in favor of manufacturing, and Japan's early recovery from the Great Depression generating an investment boom in the colony. Also Korea's cheap labor and natural resources and the introduction of controls on output and investment in Japan to mitigate the impact of the Depression helped attract direct investment in the colony. Finally, subjugating party politicians and pushing Japan into the Second World War with the invasion of China in 1937, the Japanese military began to develop northern parts of Korea peninsula as an industrial base producing munitions.

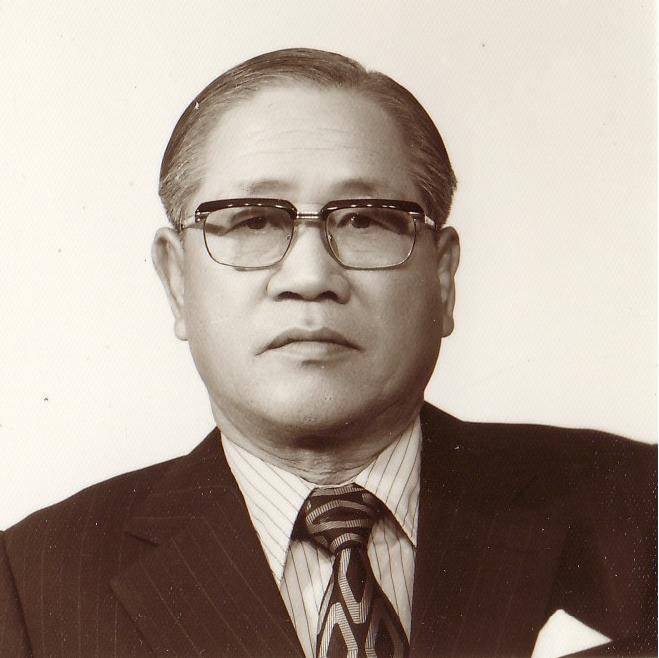

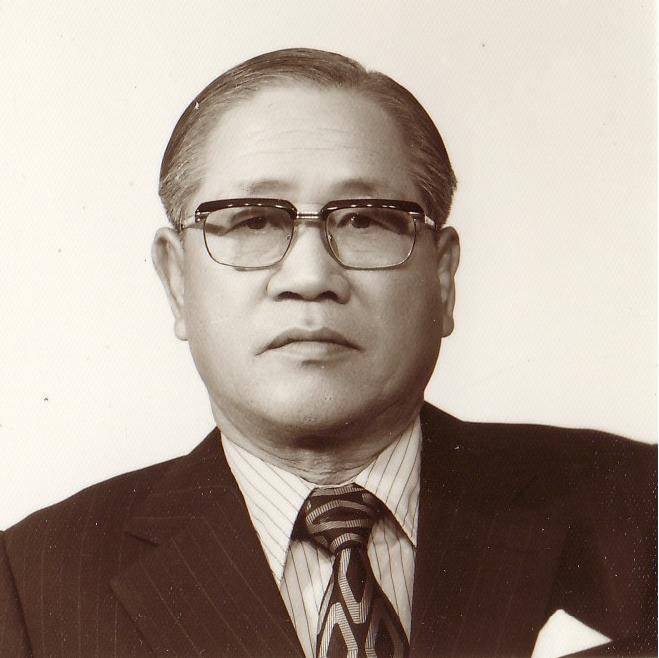

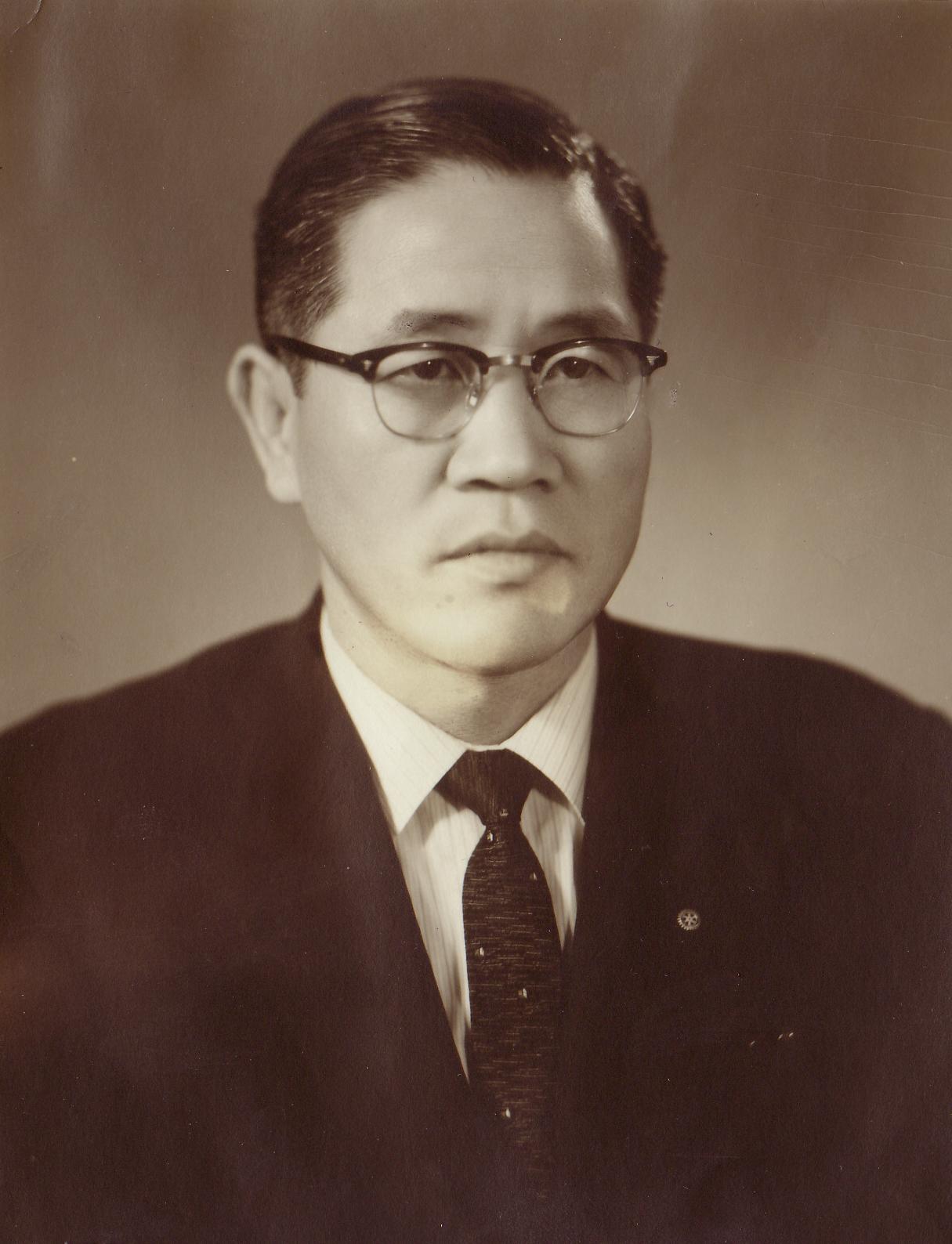

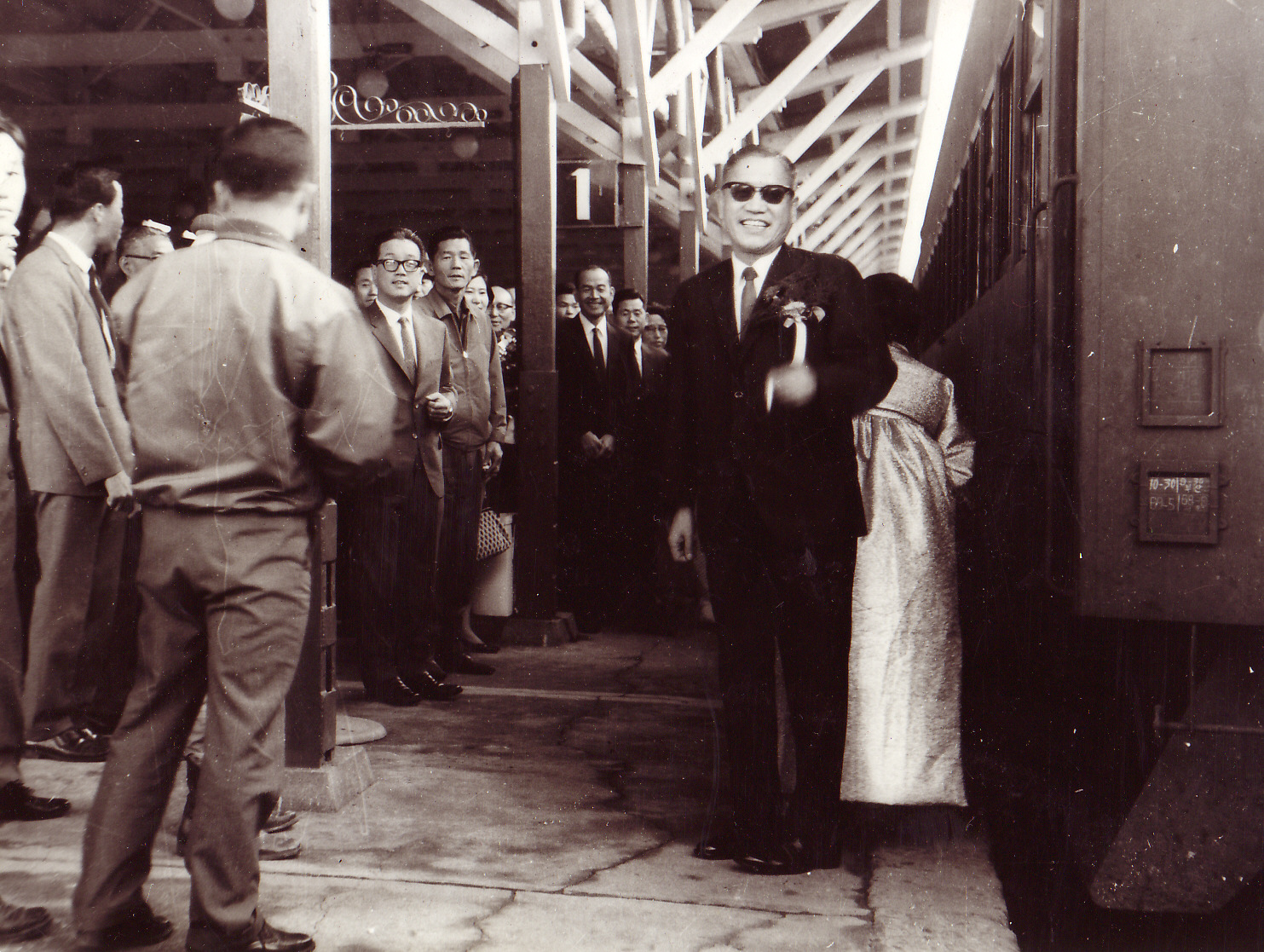

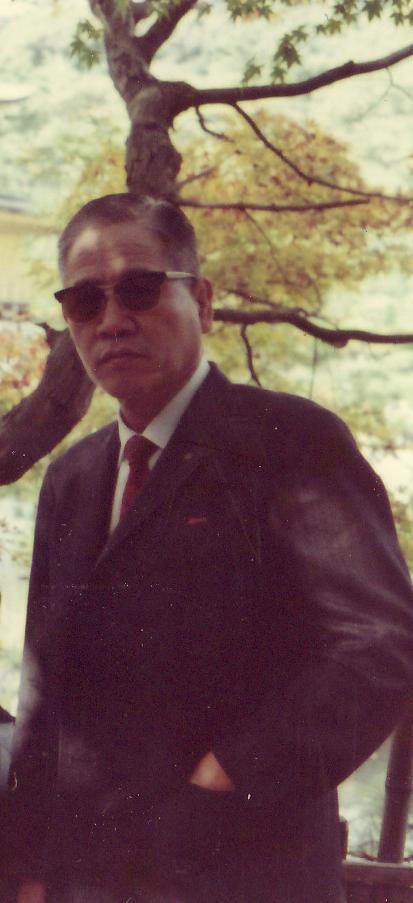

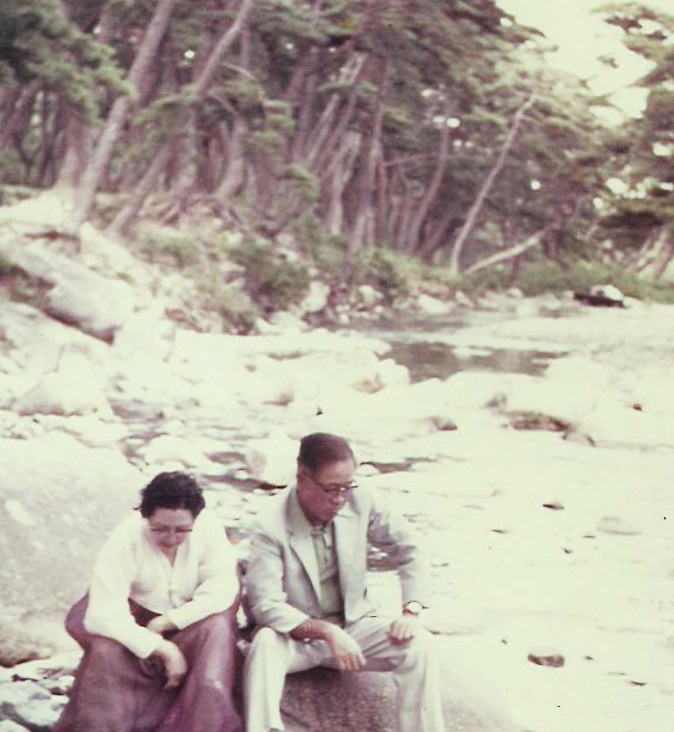

Thrown into poverty, my maternal grandfather struggled with all the problems associated with starting a business with money, connections, the horror of War in KOREA, and more. However, instead of being ground down by these hardships, he grew to be a fabulously successful entrepreneur and business leader, the founder of many companies. He started as an accountant. This position provided a good base for his business. As the Second World War, especially Pacific War broke out at 1941, he operated out of financial ventures, all this time increasing his personal holdings. In 1936, he established KyoungNam pharmaceutical company. This firm became Man-Su medicine Co., LTD. Later. He was really brilliant at business and quickly got fortune in this field. As his fortune grew, he continued to make investments and company foundations. After KyoungNam pharmaceutical company, he also established the Chosun medicine Co., LTD. in 1936 and Chosun chemical Co., LTD. in 1940. At that time, he was the Vice-Chairman of the Chamber of Chosun Commerce and Industry

With the end of the Second World War in 1945, two separate regimes emerged on the Korean peninsula to replace the colonial government. The U.S. military government took over the southern half, while communist Russia set up a Korean leadership in the northern half. The de-colonization and political division meant sudden disruption of trade both with Japan and within Korea, causing serious economic turmoil. Dealing with the post-colonial chaos with economic aid, the U.S. military government privatized properties previously owned by the Japanese government and civilians. The first South Korean government, established in 1948, carried out a land reform, making land distribution more egalitarian. After Chosun chemical Co., LTD in 1940, he also established the Dong-A chemical Co., LTD. in 1946, and funded the Dong-A University in 1946. In 1947, he established the NamSun traveling public Co., LTD. and the DaeHan-Susan Co., LTD. in 1948, and the NamChang chemical Co., LTD. in 1950.

Then the Korean Civil War broke out in 1950, killing one and half million people and destroying about a quarter of capital stock during its three year duration. When many Korean companies ran into tough times after the Korean Civil War, he saw opportunities and acquired those with potential. Throughout the 1950's, he also established many corporations and also financial foundation for academic institute. After NamChang chemical Co., LTD. in 1950, he also established the DaeHan-Gomoo trading Co., LTD. in 1951 and the Hung-An trading Co., LTD. in 1952 and the Te-il industry Co., LTD. in 1959 and the Hung-An real estate Co., LTD. in 1959 and the Korea-Samyack public corporation in 1959 and the Man-Su medicine Co., LTD. in 1964. By the mid 1950's, he had significant company holdings, and owned huge fortune by 1965. In the aftermath of the Japanese occupation of Korea which ended with Japan's defeat in World War II in 1945, he was recognized Korea and Japan as one of the most powerful businessman and provided financial backing for academic institute and private schools. In 1961, he introduced a new textile goods (Xrang) to Korea, and several other companies into the dominant textile company - the Wook-il Co., LTD. in 1965.

After the war, South Korean policymakers set upon stimulating economic growth by promoting indigenous industrial firms, following the example of many other post-World War II developing countries. The government selected firms in targeted industries and gave them privileges to buy foreign currencies and to borrow funds from banks at preferential rates. It also erected tariff barriers and imposed a prohibition on manufacturing imports, hoping that the protection would give domestic firms a chance to improve productivity through learning-by-doing and importing advanced technologies. Under the policy, known as import-substitution industrialization (ISI), entrepreneurs seemed more interested in maximizing and perpetuating favors by bribing bureaucrats and politicians, however. This behavior, dubbed as directly unproductive profit-seeking activities (DUP), caused efficiency to falter and living standards to stagnate, providing a background to the collapse of the First Republic in April 1960.

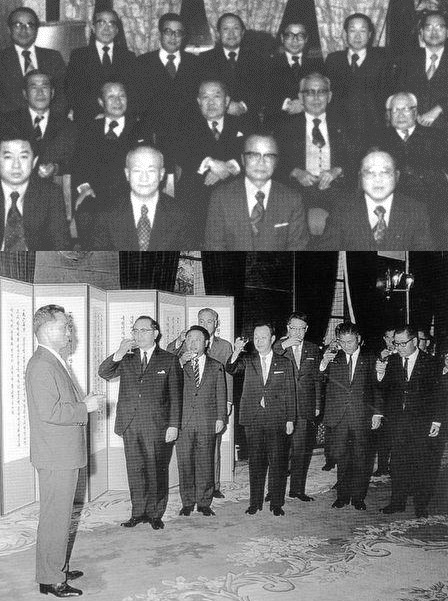

During his life, he consolidated and restructured many of his companies, bringing his own regulations and standards to an industry that the Korean government had failed to organize and control. His holdings included the trade company, medicine company, travel and bus company, textile company and chemical company, etc. While his realm expanded into many other areas, he also provided backing that assisted the local community. And, of course, anyone with as much power and influence is bound to attract his share of detractors. He was investigated and he testified in his own defense, denying charges of undue influence in his control of the country's industries and financial institutions. In spite of these things, he continued to be Korea's foremost businessman throughout his life. His accomplishments as a leader, educator, philanthropist, and management innovator are astonishing. He helped lead his country's economic miracle after Japanese invasion period, founded a university and donated hundreds of millions to good causes.

His personal wealth was enormous, and during his life he used substantial portions of his wealth in philanthropic endeavors. He donated to charities, temples, hospitals, and schools. He also accumulated a huge collection of art. When he died in 1993, many of his collection went to the Insa Gallary in SEOUL. Insadong was originally two towns whose names ended in the syllables "In" and "Sa". They were divided by a stream which ran along Insadong's current main street. Insadong began 500 years ago as an area of residence for government officials.

.jpg)

During the early period of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897), the place belonged to Gwanin-bang and Gyeonpyeong-bang - bang was the name of an administrative unit during the time - of Hanseong (old name for the capital, Seoul). During the Japanese occupation, the wealthy Korean residents were forced to move and sell their belongings, at which point the site became an area of trading in antiques. After the end of the Korean War, the area became a focus of South Korea's artistic and cafe life. It was a popular destination among foreign visitors to South Korea during the 1960s, who called the area "Mary's Alley". It gained in popularity with international tourists during the 1988 Seoul Olympics. In 2000 the area was renovated, and, after protest, the rapid modernization of the area was halted for two years beginning that year.

Insadong-gil is "well known as a traditional street to both locals and foreigners" and represents the "culture of the past and the present". It contains a mixture of historical and modern atmosphere and is a "unique area of Seoul that truly represents the cultural history of the nation."

The majority of the traditionalbuildings originally belonged to merchants and bureaucrats. Some larger residences, built for retired government officials during the Joseon period, can also be seen. Most of these older buildings are now used as restaurants or shops. Among the historically significant buildings located in the area are Unhyeongung mansion, Jogyesa - one of the most significant Korean Buddhist temples, and one of Korea's oldest Presbyterian churches.

.jpg)

His business partner - Japan Nitrogenous Fertilizer Company

The Chisso Corporation (チッソ株式社, Chisso kabushiki kaisha) is a Japanese chemical company. It is particularly well known as a supplier of liquid crystal used for LCD displays, and the cause of Minamata disease.

In 1906 Shitagau Noguchi, an electrical engineering graduate of Tokyo Imperial University, founded the Sogi Electric Company (曾木電株式社, Sogi Denki Kabushiki Kaisha) which operated a hydroelectric power station in kuchi, Kagoshima Prefecture. The power station supplied electricity for the gold mines in kuchi but had overcapacity. To make use of the surplus power in 1908 Noguchi founded the Nihon Carbide Company (日本カバイド商, Nihon Kaabaido Shkai) which operated a carbidefactory in the coastal town of Minamata, Kumamoto Prefecture, about 30 km northwest of kuchi. In the same year he merged the two companies to form the Japan Nitrogenous Fertilizer Company (日本窒素肥料株式社, Nihon Chisso Hiry Kabushiki Kaisha) - usually referred to as Nichitsu. In 1909, Noguchi purchased the rights to the Frank-Caro process, whereby atmospheric nitrogen was combined with calcium carbide (a key product of the young company) to produce calcium cyanamide, a chemical fertilizer.

Nitrogenous fertilizers were key to boosting agricultural production in Japan at the time, due to its lack of arable land and the small-scale nature of its farms, so the company found a ready market for its product. Nichitsu also branched out into other products produced from calcium carbide, beginning production of acetic acid, ammonia, explosives and butanol.

Production of ammonium sulfate (another chemical fertilizer) started in 1914 at a plant in Kagami, Kumamoto Prefecture, using a nitrogen fixation process - a Japan first. Sales of ammonium sulfate were increasing year-on-year as were market prices. A new plant was opened at the Minamata factory in 1918 where it was able to produce ammonium sulfate for 70 yen per ton and sell it for five and a half times the cost. These massive profits enabled Nichitsu to survive the subsequent drop in prices after the return of foreign competition into the Japanese market after the end of World War I in Europe in September 1918.

After the war, Noguchi visited Europe and decided Nichitsu should pioneer an alternative synthesis of ammonium sulfate in Japan. In 1924, Nichitsu's plant at Nobeoka began production using the Casale ammonia synthesis which required the use of extremely high temperatures and pressures. Once the process was proved a success, the Minamata plant was converted to the process and began mass production.

Nichitsu grew steadily, invested its profits in new technology and expanded production into new areas and slowly became a large conglomerate of many different companies.

In 1924, Shitagau Noguchi decided to expand Nichitsu into Korea. In those days, Korea was a colony of Japan. In 1926, he established two companies in Korea as subsidiaries of Nichitsu, mirroring the foundation of the parent company: Korea Hydroelectric Power Company (朝鮮水力電株式社, Chsen Suiryoku Denki Kabushiki Kaisha) and Korea Nitrogenous Fertilizer Company (朝鮮窒素肥料株式社, Chsen Chisso Hiry Kabushiki Kaisha). Noguchi wanted to repeat his success in kuchi and Minamata, but on an even greater scale in Korea.

As Japan lost the Second World War in 1945, Nichitsu and its zaibatsu collapsed and was forced to abandon all properties and interests in Korea. Furthermore, the Allies that occupied Japan ordered the dismissal of the company, regarding it as a company that adhered to the militarism government. In 1950, the New Japan Nitrogenous Fertilizer Company (新日本窒素肥料株式社 Shin Nihon Chisso Hiry Kabushiki Kaisha), usually referred to as Shin Nichitsu, was founded as a successor of the old company. Other successor companies include Asahi Kasei and Sekisui Chemical. In addition, Chisso had American photographer and photo-journalist W. Eugene Smith beaten by yakuza goons after Smith published a highly regarded photo-essay showing the caustic injuries and birth defects Chisso had caused the Minamata population. The centerpiece of the work, titled "Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath", depicted the severe deformation of a child in her mother's arms after the child was exposed to the effects of Chisso's contamination of the water supply. In response to Chisso's beating of W. Eugene Smith for dissemination of the photographs, Smith was awarded the Robert Capa Gold Medal in 1974 for "best published photographic reporting from abroad requiring exceptional courage and enterprise".

.jpg)

His business partner - Ataka & Co. Ltd,.

The company, Ataka & Co., Japan's ninth largest trading company, and Kyoei Steel Ltd., a medium-sized Japanese firm specializing in mini mills. The building of this "first" Japanese steel mill in a small, obscure city in the rolling hills of Central New York State, near Syracuse, is interpreted by some economists with expertise in Japanese multi-national business practices, as variously a symbol of corporate prestige for the companies involved and as a good will gesture from the Land of the Rising Sun.

The city's energetic mayor, Paul Lattimore, who played a pivotal role in bringing the Japanese to Auburn, views the mill as the fulfillment of an idea that blossomed in his mind at 3 o'clock one cold winter's morning five years ago. "The minute I wake up, I'm up," Lattimore said. "This night I was reading in the Wall Street Journal about the world wide growth of mini mills. When I read it, I decided we ought to be able to build one here."

.jpg)

The mayor is of the genre of politician forever scanning the horizons for a basic industry that could bring jobs, business and prosperity to his community. That propensity is magnified in Auburn by the city's perennial high unemployment rate whose beginnings are traced by some back to 1948 when International Harvester Co. closed a farm machinery plant throwing 2,000 local residents out of work. In ensuing years, other major factories folded as Auburn began suffering from what Associate Professor Yoshi Tsrumi of the Harvard Business School describes as "deindustrialization."

Late in January, 1971, Lattimore told a reporter for the Auburn Citizen-Advertiser about his concept of the mini mill for Auburn. Through the Auburn Industrial Development Authority, which the mayor heads, the Battelle Memorial Institute was hired to conduct a feasibility study at a cost of $34,000. "I instructed Battelle to take the hard-nosed position of the investor," Lattimore said, adding: "The conclusion was that it was feasible." Lattimore arranged for the Commerce Department to distribute the Battelle study through commercial attaches in U.S. embassies overseas in the spring of 1972.

Kyoei Steel of Osaka, Japan was the first company to reply to Lattimore answering in a letter dated May 24, 1972. By coincidence, Lattimore already was preparing to travel to Japan to confer with an automobile manufacturer in hopes of attracting it to build in Auburn. He simply included a visit to Osaka in his itinerary. Back home in Auburn, Lattimore's political opposition criticized the trip abroad as "junket" and a "scatterbrained" scheme. The skeptical attitude was supported by the failure of the mayor's past efforts to deliver new industrial jobs to the city.

South Korea's economy was small and predominantly agricultural well into the mid-20th century. However, the policies of President Park Chung Hee spurred rapid industrialization by promoting large businesses, following his seizure of power in 1961.

This was called the First Five Year Economic Plan. Government industrial policy set the direction of new investment, and the chaebol were to be guaranteed loans from the banking sector. In this way, the chaebol played a key role in developing new industries, markets, and export production, helping place South Korea as one of the Four Asian Tigers. Although South Korea's major industrial programs did not begin until the early 1960s, the origins of the country's entrepreneurial elite were found in the political economy of the 1950s. Very few Koreans had owned or managed larger corporations during the Japanese colonial period. After the departure of the Japanese in 1945, some Korean businessmen obtained the assets of some of the Japanese firms, a number of which grew into the chaebol of the 1990s. These companies, as well as certain other firms that were formed in the late 1940s and early 1950s, had close links with Syngman Rhee's First Republic, which lasted from 1948 to 1960. It was alleged that many of these companies received special favors from the government in return for kickbacks and other payments.

.jpg)

When the military took over the government in 1961, military leaders announced that they would eradicate the corruption that had plagued the Rhee administration and eliminate injustice from society. Some leading industrialists were arrested and charged with corruption, but the new government realized that it would need the help of the entrepreneurs if the government's ambitious plans to modernize the economy were to be fulfilled. A compromise was reached, under which many of the accused corporate leaders paid fines to the government. Subsequently, there was increased cooperation between corporate and government leaders in modernizing the economy. Government-chaebol cooperation was essential to the subsequent economic growth and astounding successes that began in the early 1960s. Driven by the urgent need to turn the economy away from consumer goods and light industries toward heavy, chemical, and import-substitution industries, political leaders and government planners relied on the ideas and cooperation of the chaebol leaders. The government provided the blueprints for industrial expansion; the chaebol realized the plans. However, the chaebol-led industrialization accelerated the monopolistic and oligopolistic concentration of capital and economically profitable activities in the hands of a limited number of conglomerates. Park used the chaebol as a means towards economic growth. Exports were encouraged, reversing Rhee's policy of reliance on imports. Performance quotas were established.

.jpg)

The chaebol were able to grow because of two factors—foreign loans and special favors. Access to foreign technology also was critical to the growth of the chaebol through the 1980s. Under the guise of "guided capitalism," the government selected companies to undertake projects and channeled funds from foreign loans. The government guaranteed repayment should a company be unable to repay its foreign creditors. Additional loans were made available from domestic banks. In the late 1980s, the chaebol dominated the industrial sector and were especially prevalent in manufacturing, trading, and heavy industries.

The tremendous growth that the chaebol experienced, beginning in the early 1960s, was closely tied to the expansion of South Korean exports. Growth resulted from the production of a diversity of goods rather than just one or two products. Innovation and the willingness to develop new product lines were critical.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, chaebol concentrated on wigs and textiles; by the mid-1970s and 1980s, heavy, defense, and chemical industries had become predominant. While these activities were important in the early 1990s, real growth was occurring in the electronics and high-technology industries. The chaebol also were responsible for turning the trade deficit in 1985 to a trade surplus in 1986. The current account balance, however, fell from more than US$14 billion in 1988 to US$5 billion in 1989. The chaebol continued their explosive growth in export markets in the 1980s. By the late 1980s, the chaebol had become financially independent and secure—thereby eliminating the need for further government-sponsored credit and assistance. By the 1990s, South Korea was one of the largest NICs, and boasted a standard of living comparable to industrialized countries. President Kim Young-sam began to challenge the chaebol, but it was not until the Asian financial crisis in 1997 that the weaknesses of the system were widely understood. Of the 30 largest chaebol, 11 collapsed between July 1997 and June 1999. Initially, the crisis was caused by sharp drop in the value of the currency, and aside from immediate cash flow concerns for paying foreign debts, this lower cost ultimately helped the stronger chaebol expand their brands to western markets, but with the simultaneous decline of nearby export markets in Southeast Asia which had been fueling growth, the large debts incurred for what was now overcapacity proved fatal to many of the chaebol.

The remaining chaebol also became far more specialized in their focus. For example, with a population only ranked at #26 in the world, before the crisis, the country had seven major automobile manufacturers, and after only two major manufacturers remained intact, though two additional continued, in a smaller capacity, under General Motors and Renault. The chaebol debts were not only to state industrial banks, but to independent banks and their own financial services subsidiaries. The scale of the loan defaults meant that banks could neither foreclose nor write off bad loans without themselves collapsing, so the failure to service these debts quickly caused a systemic banking crises, and South Korea was forced to turn to the IMF for assistance. The most spectacular example came in mid-1999 with the collapse of the Daewoo Group, which had some US$80 billion in unpaid debt. At the time, it was the largest corporate bankruptcy in history. Investigations also exposed widespread corruption in the chaebol, particularly fraudulent accounting and bribery. Despite this, South Korea recovered quickly from the crisis, and most of blame for the economic problems was shifted to the IMF. The remaining chaebol have grown substantially since the crisis, but they have maintained far lower debt levels.

The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, as its name suggests, is a museum dedicated to collecting, exhibiting, and researching oriental ceramics. Founded by the City of Osaka in 1982, the Museum has been in operation now for 17 years. Since its founding, the Museum has gone through many changes. The changes we have undergone are related to the enrichment of our collection through donations and acquisitions. Expansion of the content of our collection naturally led to the need to expand the Museum's facilities to contain it. Fortunately, we were able to realize the construction of a new annex to the Museum. Construction began in March 1997 and was completed in September 1998, and the new annex opens in March 1999. The original Museum at the time of its opening had a total floor area of 2500 square meters. The new annex has a floor area of 1423 square meters, meaning that we have increased our space by nearly 60 percent.

As I will discuss later, the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka was originally built to house the Ataka Collection. The new annex will contain the following four galleries.

First, the permanent gallery of the RHEE Byung-Chang Collection of Korean ceramics; second, the permanent gallery of the Museum's collection of Japanese ceramics; third, a special gallery to exhibit works which have been donated to the Museum apart from the Ataka Collection and RHEE Byung-Chang Collection; and fourth, a Reference Gallery of ceramic materials.

Regarding the RHEE Byung-Chang Collection, a detailed catalog, "Color of Elegance, Simplicity of Form - The Beauty of Korean Ceramics from the RHEE Byung-Chang Collection," has been separately published, so I will limit myself here to a brief overview. Dr. RHEE Byung-Chang is a Korean national who has lived in Japan since 1949. His career included serving as a diplomat, obtaining a doctorate in economics, and operating a trading company. Dr. RHEE spent half of his life assembling a collection of 301 pieces of Korean ceramics and 50 pieces of Chinese ceramics. He spent a long time carefully considering where to leave his collection and how to put it to the best use; as a result of his deliberation, he decided to donate the entire collection to the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka. His goal is to provide a source of courage and pride to Koreans living in Japan, and also to tell the world about the object of his boundless passion, the beauty and fascination of Korean ceramics.

To help realize this goal, Dr. RHEE also donated land and a house he owned and lived in for many years in Moto-azabu, Minato Ward, Tokyo to the Museum to provide funds for research of Korean ceramics. In terms of quality, Dr. RHEE's collection of Korean ceramics is among the world's top private collections. The addition of the Rhee Collection to the Ataka Collection is of immeasurable value in enriching the quality of the Museum's overall collection. Thanks to the generosity of Dr. RHEE Byung-Chang and his wife, Dr. Madeleine KIM, the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka is now the world's foremost center for the appreciation and research of Korean ceramics outside of Korea itself.

The next gallery, the Japanese Ceramics Gallery, has been a long-standing issue since the Museum's founding. The Ataka Collection is centered around Korean and Chinese ceramics, and includes only one or two pieces of Japanese ceramics. The resulting situation meant that the "Museum of Oriental Ceramics" was not able to live up to its name. In response to strong appeals from Japan and overseas, in 1992 the Museum began collecting Japanese works. Although small, we have finally assembled a collection which is worthy of permanent display. At present, as a collection it is still incomplete, but we intend to continue to add to it in the future.

Third, in addition to the 965 pieces of the Ataka Collection and 351 pieces of the RHEE Byung-Chang Collection, many people have generously donated works to the Museum. The number of such donations now totals 333 items. In the Special Gallery, as a way of repaying the generosity of the donors, we will exhibit these works on a rotating basis according to a yearly schedule.

In addition to the pieces of ceramic art which we exhibit, the Museum has a large collection of ceramic reference materials. We wish these to be put to wide use, and we will make them freely available to those who are interested such as researchers, students, and ceramic artists. The Reference Gallery was established for this purpose; the details of managing the gallery have yet to be worked out, however, and for the time being the gallery will be opened for limited periods of time.

South Korea's real gross domestic product expanded by an average of more than 8 percent per year, from US$2.7 billion in 1962 to US$230 billion in 1989, breaking the trillion dollar mark in 2007. Nominal GDP per capita grew from $103.88 in 1962 to $5,438.24 in 1989, reaching the $20,000 milestone in 2007. The manufacturing sector grew from 14.3 percent of the GNP in 1962 to 30.3 percent in 1987. Commodity trade volume rose from US $480 million in 1962 to a projected US $127.9 billion in 1990. The ratio of domestic savings to GNP grew from 3.3 percent in 1962 to 35.8 percent in 1989.

The most significant factor in rapid industrialization was the adoption of an outward-looking strategy in the early 1960s. This strategy was particularly well-suited to that time because of South Korea's poor natural resource endowment, low savings rate, and tiny domestic market. The strategy promoted economic growth through labor-intensive manufactured exports, in which South Korea could develop a competitive advantage. Government initiatives played an important role in this process. The inflow of foreign capital was greatly encouraged to supplement the shortage of domestic savings. These efforts enabled South Korea to achieve rapid growth in exports and subsequent increases in income.

By emphasizing the industrial sector, Seoul's export-oriented development strategy left the rural sector relatively underdeveloped. Except for mining, most industries were located in the urban areas of the northwest and southeast. Heavy industries generally were located in the south of the country. Factories in Seoul contributed over 25 percent of all manufacturing value-added in 1978; taken together with factories in surrounding Gyeonggi Province, factories in the Seoul area produced 46 percent of all manufacturing that year. Factories in Seoul and Gyeonggi Province employed 48 percent of the nation's 2.1 million factory workers. Increasing income disparity between the industrial and agricultural sectors became a serious problem by the 1970s and remained a problem, despite government efforts to raise farm income and improve rural living standards.

In the early 1980s, in order to control inflation, a conservative monetary policy and tight fiscal measures were adopted. Growth of the money supply was reduced from the 30 percent level of the 1970s to 15 percent. Seoul even froze its budget for a short while. Government intervention in the economy was greatly reduced and policies on imports and foreign investment were liberalized to promote competition. To reduce the imbalance between rural and urban sectors, Seoul expanded investments in public projects, such as roads and communications facilities, while further promoting farm mechanization.

The measures implemented early in the decade, coupled with significant improvements in the world economy, helped the South Korean economy regain its lost momentum in the late 1980s. South Korea achieved an average of 9.2 percent real growth between 1982 and 1987 and 12.5 percent between 1986 and 1988. The double digit inflation of the 1970s was brought under control. Wholesale price inflation averaged 2.1 percent per year from 1980 through 1988; consumer prices increased by an average of 4.7 percent annually. Seoul achieved its first significant surplus in its balance of payments in 1986 and recorded a US $7.7 billion and a US $11.4 billion surplus in 1987 and 1988 respectively. This development permitted South Korea to begin reducing its level of foreign debt. The trade surplus for 1989, however, was only US $4.6 billion, and a small negative balance was projected for 1990

Textiles and other labour-intensive industries have declined from their former preeminence in the national economy, although they remain important, especially in export trade. Heavy industries, including chemicals, metals, machinery, and petroleum refining, are highly developed. Industries that are even more capital- and technology-intensive grew to importance in the late 20th century—notably shipbuilding, motor vehicles, and electronic equipment. Emphasis was given to such high-technology industries as electronics, bioengineering, and aerospace, and the service industry grew markedly. Increasing focus has been placed on the rise of information technology and the promotion of venture-capital investment. Much of the country’s manufacturing is centred on Seoul and its surrounding region, while heavy industry is largely based in the southeast; notable among the latter enterprises is the concentration of steel manufacturers at P’ohang and Kwangyang, in the southeast.

The Korea Development Institute also forecasted in 1988 that South Korea's per capita GNP would exceed US $10,000 early in the twenty-first century. The institute predicted that Seoul would enjoy a higher sustained growth rate than average through the 1990s; that the manufacturing industry would play a pivotal role in the economy in the twenty-first century; and that the service industry would become knowledge-intensive in order to meet the needs of a highly diversified industrialized society. The share of the primary sector (agriculture, forestry, and fisheries) would sink to nearly 5 percent by the turn of the century, whereas the secondary sector (industry) would rise to over 40 percent and the service sector would be at about 55 percent. Major areas of industrial growth would include automobiles, electronics, and machinery.

In 1988 Kim Duk-choong of Sogang University listed five main points that were expected to make the "Korean economic future look bright." He noted that South Korea had drastically reduced its foreign debts since 1985, greatly increased the rate of domestic savings, improved on the equitable distribution of income throughout the population, increased the role of small and medium-sized corporations in the economy, and made the transition from a labor-oriented to a technology-oriented economy. He expected that these positive economic developments would easily outweigh existing problems and lead to real growth in years to come.

Kim's optimism had merit, but there were other important issues that could inhibit economic growth, for example, rising protectionist sentiments in the United States, Japan, and elsewhere. Moreover, as South Korea moved up the technological ladder, it would face stiff competition from advanced nations like Japan and up-and-coming nations like Thailand. There also was the intangible problem of the resolve of South Korea's workers, who labored six days a week with little vacation time. What effect would a slackening of resolve have on the South Korean worker by the 2000.

In the aftermath of the Korean War, South Korea became increasingly authoritarian as a result of militant anti-Communist policies enacted by President Syngman Rhee. Despite these issues, the Rhee administration is noted for at least two achievements that aided economic growth. First, Rhee's firm leadership in the aftermath of the war allowed South Korea to stabilize itself. Secondly, the Rhee administration implemented an important land reform that provided for the redistribution of land, averting a potentially explosive social issue. However, when Rhee and the Liberal Party rigged the presidential election of 1960 in an attempt to consolidate their power, nationwide demonstrations led by angry students brought about the end of Rhee's regime, to be succeeded democratically by Chang Myon, the leader of the Democratic Party.

One of the most important contributors to the "Miracle on the Han River" was Park Chung-Hee. Under the rule of Park Chung-hee, South Korea began to make a successful recovery in its economy. Park Chung-hee announced the first 5-year Economic Development Plan to mobilize national resources in establishing a self-supporting industrial economy. This psychological boost gave Koreans confidence and motivation in its path to economic success."Treat employees like family" was Park's new motto, which also led to Korea's economic success. With this motto, Korean workers were claimed to be 2.5 times more productive than American workers even though Korean workers were paid one-tenth of American wages.

Park's rule is remembered by Koreans with mixed emotions. Many praise him for the contributions he made to Korea's economy and its recovery, but contemporary opinions criticize him for systematically disregarding human rights and censoring the media as part of a brutal military dictatorship. Following a military coup in the 1960s Park established a strong authoritarian rule characterized by a one-party regime. In this authoritarian state, the leading party only had to appease a small constituency of the ruling or military elite. During Park's tenure Korea suffered from censorship in the press and media. Because of strong antipathies toward communism, Korean journalism and free speech were tightly controlled. Disregarding human rights and violations, Park would utilize the abundant supply of cheap labor and place his foremost priority on Korea's economic restoration. Morality laws established mandatory curfews and regulations on attire and music.

In his program of Yushin Kaehyuk (Revitalizing Reforms), he caused Korean cinema to enter into a moribund period considered by many to be the lowest periods in the history of Korean cinema.

Such enormousgrowth of economy came with costs to freedom. Although Park was successful in bringing economic recovery to Korea, he trampled on human rights and often imprisoned those who questioned his rule. Park had believed that South Korea was not ready to be a full democratic nation nor a free nation. As he stated,"Democracy cannot be realized without an economic revolution."

Park argued that the poverty of the nation would make it vulnerable, and therefore an urgent task was to eliminate poverty rather than establish a democratic nation. During his presidency the Korean Central Intelligence Agency became a much feared institution and the government frequently imprisoned anyone who opposed them. Park Chung-hee's rule ended on October 26, 1979 when he was killed by his chief of security services, Kim Jaegyu.

Despite ongoing pressure from North Korea, President Park Chung Hee formulated a 5-year plan to boost the South Korea economy with several goals: develop energy industries (such as coal production and electric power) expand agricultural production and aimed at increasing farm income and correcting the structural imbalance of the national economy develop basic industries and the economic infrastructure utilize to the full extent of idle resource; increased employment; conservation and utilization of land improve the balance of payments through export promotion promote science and technology.

While this 5-year plan did not bring about an immediately self-reliant economy, there was a rapid period of growth out of this policy. The ambitious plan had simply looked for better policies in modernizing and preparing for long-term economic success. The government's efforts were designed to bring about policy reform.

He, my grandfather, also made significant contributions to the welfare of South Korea. South Korea began a strong economic recovery after this point and South Korea eventually became the 11th largest economy in the world with a per capita income exceeding $10,000 per year and more than 70% of its population claiming to be middle class.

At the root of the rapid expansion of the Korean national economy were several factors, some societal and others political. One acclaimed building block of the "Miracle on the Han" was the importance placed on education. Aided by traditional Confucian ideals which celebrated literacy and scholarship, the state established a public compulsory education system. This allowed Korean labor to become highly skilled while labor expenses remained relatively low.

Three other key factors (known as “The Iron Triangle”) for the country's regeneration were state strength, strong bureaucracy, and the Korean Chaebol businesses. Park’s government combined national and private economic interests in a way that manipulated nationalistic sentiments, allowing the government to push through economic policies. These policies were incorporated in several ways, including policy loans, which were utilized to stimulate the struggling economy. The implementation of the policies resulted in state-sponsored industrialization and commercial expansion

The last but not the least, I cannot end without thanking my paternal and maternal grandparents. Words cannot truly express my deepest gratitude and appreciation to them. I hope they are looking down from somewhere with a smile. Definitely, they are remembered and accepted by me, now and forever.